During the coronation, one or two of us may feel as if we are taking everything a little too seriously. We may become overly concerned in obscure topics concerning hereditary peerage or the Crown jewels. We may discover, to our surprise, that we are deeply affected by the Westminster Abbey ceremony and want it to go well. And we may be perplexed as to how to respond to intellectuals who claim the entire situation is irrational and undemocratic. Because, in the midst of the splendour, or flummery as intellectuals would call it, the practical purpose of the monarchy is easily overlooked. The King is not an enemy of democracy, but rather its guardian.

According to the law, the military services, judges, Members of Parliament, aspirants for British citizenship, and many others must pledge allegiance to King Charles, his heirs, and successors. The monarch fills the role that a dictator would need to fill.

On Saturday, September 10, 2022, two days after Queen Elizabeth II’s death, the King declared that he will “strive to follow the inspiring example I have been set in upholding constitutional government,” will be “supported by the affection and loyalty of the peoples whose Sovereign I have been called upon to be,” and “will be guided by the counsel of their elected parliaments.”

The King has no say over who becomes prime minister. That authority is held by the Commons, which is highly sensitive to public opinion even when no general election is on the horizon. In recent years, great care has been taken to limit the Sovereign’s residual right, or obligation, to choose between rival candidates for the prime ministership. Political parties may get this wrong, but it is their fault if they do. The king is above politics, and when the government becomes unpopular, as it frequently does, we blame the prime minister and fire him or her.

In the year 1875, a great historian with radical tendencies, Frederic Harrison, could already write: “England is now an aristocratic Republic, with a democratic machinery and a hereditary grandmaster of the ceremonies.” Walter Bagehot had labeled England a “disguised republic” ten years before. Parliament has long been on the rise. As part of the price for backing the Protestant William III and his wife, Mary II, who drove out her father, the Catholic James II, it established the concept that the Crown could not tax without Parliament’s agreement or meddle in parliamentary elections in 1689. Twelve years later, when neither Mary nor her sister, Queen Anne, had produced a surviving Protestant successor, Parliament passed the Act of Settlement, which barred any Catholic contenders to the throne, the Act of Settlement, the presumption being that only a Protestant king could be trusted to defend his subjects’ ancient liberties. So when Anne died in 1714, the throne passed to George I, of the House of Hanover, who did not speak English very well.

Commentators who assert that we are “in thrall” to kings and queens are incorrect. Only 87 years ago, our politicians, led by then-Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, forced the abdication of Edward VIII, whose refusal to marry Mrs Simpson, an American with two former husbands still alive, was deemed unacceptable. True, we did not seize the opportunity to abolish the monarchy entirely. When a fiery Clydesider, James Maxton, suggested in the Commons as an amendment to the Abdication Bill that Britain become a republic, the motion was defeated by a vote of 403 to 5. The country desired a conscientious ruler, which George VI eventually became. On December 12, 1936, he declared his “adherence” in his Accession Council.

But how dull a purely conscientious monarchy would be. As Bagehot remarked in the Economist in the mid-19th century, “The more democratic we get, the more we shall get to like state and show, which have ever pleased the vulgar.” Part of the point of the monarchy is to put on a splendid show. Eric Hobsbawm, a communist rather than a monarchist, well understood this. In his essay on the mass production of traditions in Europe from 1870 to 1914 he wrote: “Glory and greatness, wealth and power, could be symbolically shared by the poor through royalty and its rituals.” By magnifying the monarch, we magnify ourselves.

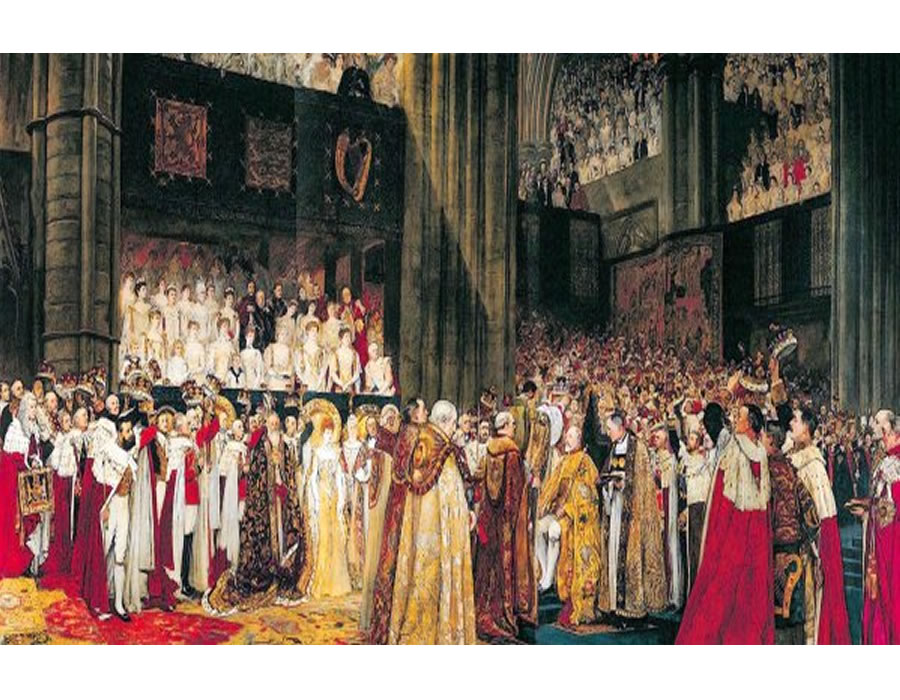

George IV, King from 1820-30 and before that Prince Regent, received, even in his lifetime, a very bad press, but revelled in the opportunity to put on a good show. In July 1821 he was crowned in an immensely extravagant ceremony organised by himself with the help of the novelist Sir Walter Scott, the intention being to show that the British monarchy was more magnificent than Napoleon had ever been. The King’s estranged wife, Queen Caroline, whom the public loved, attempted to gain entrance to Westminster Abbey, but was turned away on the typically English pretext that she had no ticket.

The monarchy is not just about being conscientious as it is important for the monarch to put on a splendid show to please the public. Eric Hobsbawm recognized this aspect, and the mass production of traditions in Europe from 1870 to 1914 allowed the poor to symbolically share in glory, greatness, wealth, and power through royalty and its rituals. The monarch represents the magnification of the people. The coronations of George IV, William IV, Queen Victoria, and Edward VII are examples of how British ceremonial changed over time. While slipshod behavior worked out for the best during Victoria’s coronation, it was understood by the time Edward VII ascended the throne in 1901 that such behavior was no longer acceptable. The coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 was the first great spectacle of the television age, with a huge audience able to follow the event due to Richard Dimbleby’s commentary.

The monarchy’s significance lies in its ability to provide the public with a grand display of pomp and circumstance.